|

The phrase “got your nose,” often accompanied by the pretend seizing of the nose, is part of a quaint childhood game. But wouldn’t it be quite useful if we really could transport our sense of smell elsewhere to help recognize different fragrances or even odors that we do not typically detect? If we could safely use the sense of smell to identify unfamiliar scents in our surroundings, we could be alerted to potential dangers like chemical spills or even trace the location of a lost person.

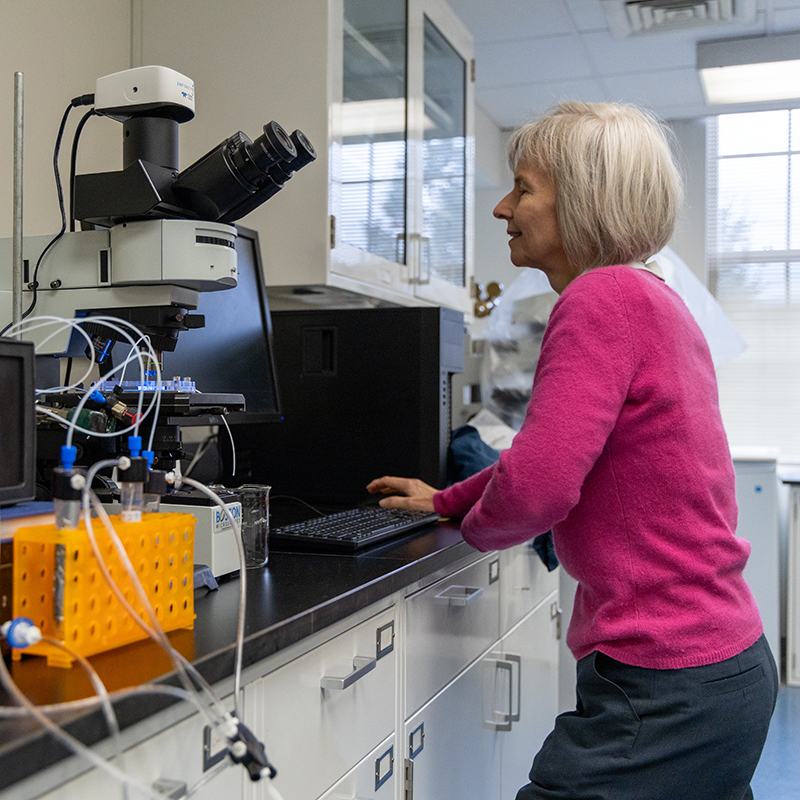

This is the ambitious goal of the “bio-nose” project led by mechanical engineering professor Elisabeth Smela and an interdisciplinary team: biology professor Ricardo Araneda, electrical and computer engineering professor Pamela Abshire, science, technology and society program director David Tomblin, and computer science and UMIACS professor Abhinav Shrivastava. Backed by a National Science Foundation (NSF) grant of $2 million in funding over four years, the team aims to create a portable device capable of identifying odors in the built environment.

“If we had handheld devices that could recognize complex odors, a lot of things would be possible,” said Smela. “There are applications in food, wine, perfumes, medical diagnostics, homeland security, agriculture, mold detection, and more.”

In nature, animal species, including dogs, humans, and insects, have an extraordinary capacity for olfaction, allowing them to distinguish an extensive array of odors across different environments. To take advantage of nature’s capacity for olfactory reception and scent recognition, this team is working on developing a cell-based sensor. However, in the past, using cells for this type of application has been challenging. For example, mammalian cells need to be fed and held at body temperature to be kept alive.

“Think about the yeast that you keep dried at home. Wouldn’t it be nice if we had some cells that we could keep dry until we were ready to use them?” Smela questioned.

The team’s collaborators at the National Agriculture and Food Research Organization (NARO), an institute in Japan, created an insect-based cell line capable of just that. The cells can be desiccated, or dried, and then re-animated with the addition of fluid. And because the cells are from an insect, they can be cultured at room temperature. These cells don’t normally express olfactory receptors, so the NARO researchers added the necessary genes into the cell line.

Currently, the team is studying how the cell line responds when it is introduced to different liquid odorants. This is just one step of many on the way to developing a fully usable bio-nose device. Some future challenges include investigating methods for introducing airborne odorants and using machine learning to identify the spatio-temporal patterns generated by a collection of different cells when exposed to various odors.

“The addition of biological components to technology as well as the positive impact that an artificial nose could have on people’s lives makes this research particularly exciting,” said Smela.

Related Articles:

New Initiatives Push Toward Safe & Reliable Autonomous Systems

Tuna-Inspired Mechanical Fin Could Boost Underwater Drone Power

State-of-the-Art 3D Nanoprinter Now at UMD

Das Named Pioneering Researcher by Chemical Communications

Groth Part of $10 Million DOE Hydrogen Grant

Dutt Receives NSF CAREER Award

UMD’s Zhao to Lead New Dynamic PRA Study

McGregor: Harnessing the Potential of Additive Manufacturing

MARC Program Now Accepting Applications

In Soft Robotics, Instability Can Be a Plus

September 28, 2023

|