|

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread in early 2020, musicians and band directors were quick to realize the implications for live music. In order for bands and vocalists to resume practicing and performing together in person, more needed to be known about the risks—and how to mitigate them.

But only scant data existed on how instruments, including the human voice, spread particles into the surrounding space.

To fill in the knowledge gap, two leading organizations of music educators—the College Band Directors’ National Association and the National Federation of State High School Associations—teamed up to commission a pair of studies, led respectively by the University of Colorado-Boulder’s Shelly Miller and University of Maryland (UMD) mechanical engineering professor Jelena Srebric, who is acting associate dean of research at the A. James Clark School of Engineering.

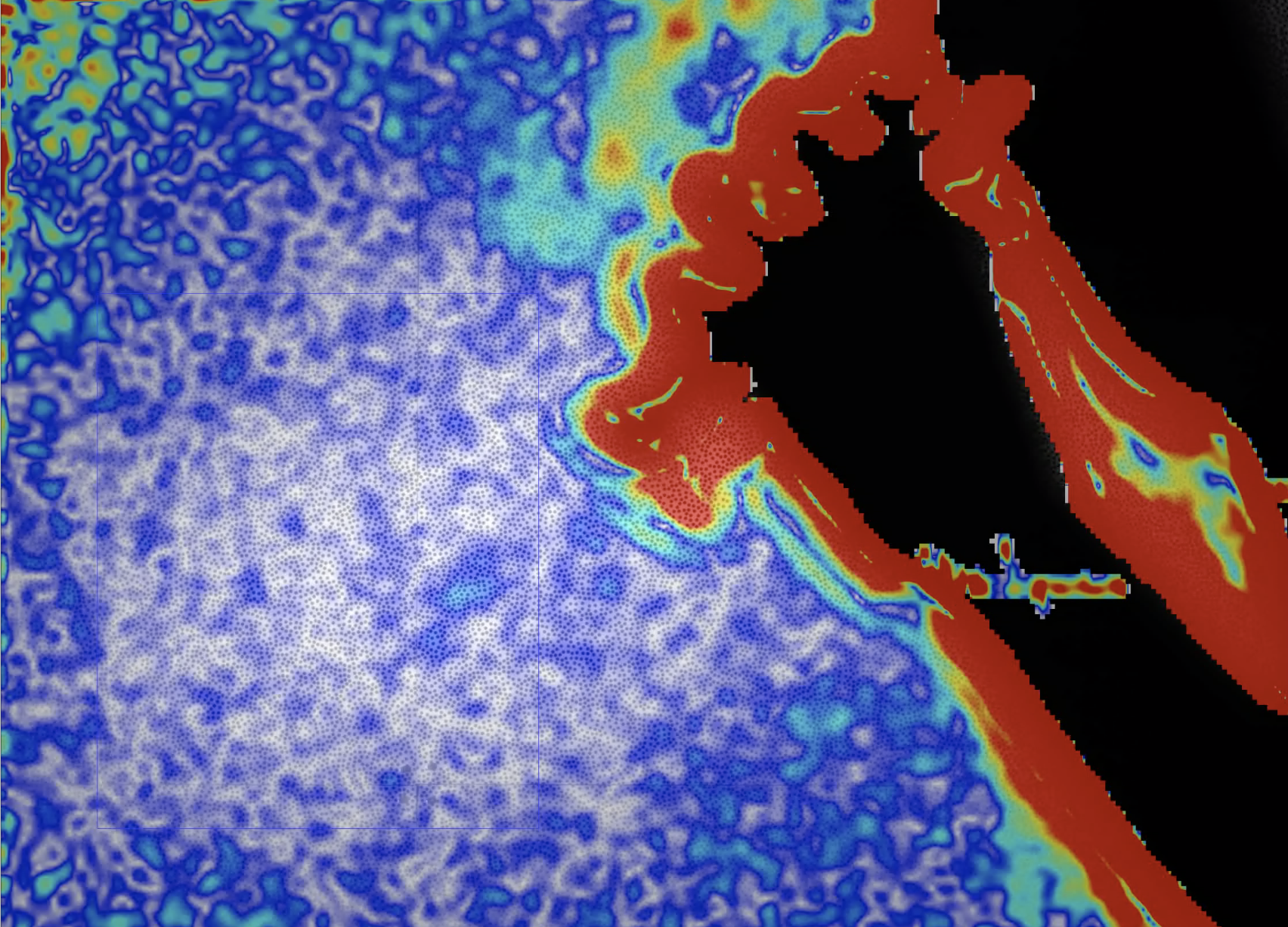

The goal: conduct tests to measure the behavior of particles emitted when a brass player sounds a note, or when a soprano lifts her voice in song.

“The more we understand about the trajectory of aerosols in situations such as indoor rehearsals and concerts, or outside at a sporting event, the more we’ll be able to devise methods for keeping performers and spectators safe, while enabling us to continue to enjoy live music,” Srebric said. “The more we understand about the trajectory of aerosols in situations such as indoor rehearsals and concerts, or outside at a sporting event, the more we’ll be able to devise methods for keeping performers and spectators safe, while enabling us to continue to enjoy live music,” Srebric said.

Working out of a specially equipped chamber near UMD’s College Park campus, Srebric and her team have been running tests on clarinets, euphoniums, flutes, French horns, oboes, saxophones, trombones, trumpets and tubas, while also measuring the aerosols emitted by actors and vocalists.

With two sets of preliminary results released so far, the studies have yielded some cause for optimism: while playing wind and brass instruments, along with vocal performances, can indeed become vectors for virus transmission, the risk can be reduced by an impressive degree through the use of protective measures.

Instruments vary considerably when it comes to aerosol emissions, the researchers found. The oboe, for instance, is a particle powerhouse—thanks to the high-pressure action of its double reeds. Flutes, despite their breathy timbre, turn out to send relatively few particles into the surrounding air, although those particles are spread directly to the right at face level.

Meanwhile, actors and vocalists alike can fill a space with aerosols, particularly at moments of peak intensity (as in a declaimed monologue, pop song or hymn).

The good news: in all cases, emissions can be cut to safer levels by performing with a mask on—or, in the case of wind and brass instruments, using a bell cover with the musician wearing a modified instrument mask. For instruments that do not accommodate bell covers, such as the flute, then the musician can wear a face shield and a plexiglass barrier to their right could be installed. Based on the studies’ findings, the sponsoring organizations have drawn up guidelines—supplemented with posters and videos—for schools, colleges, and other organizations involved with live music.

For Srebric, there is satisfaction in knowing her work will be put to immediate, practical use. “It’s such a great cause,” she said. “A world without live music is no good!”

Kelsey Eustace contributed to this article.

Related Articles:

Safe Storage

UMD Engineers Help Pioneer New Treatment for Respiratory Failure

A Tech Rx for COVID Recovery at Home

UMD developing COVID-19 decision making tools for colleges

Aerosol Containment Chamber to Make COVID-19 Intubations Safer

Better, Cheaper COVID-19 Tests

Researchers Design Mobile COVID-19 Testing Booths

Forecasting COVID-19: New UMD Research Could Help

Clark School Engineers 3D Print Protective Face Shields

Srebric, Colleagues Win Best Paper Award

September 21, 2020

|